Arizona is one of 11 states that doesn’t compensate people after wrongfully convicting them. State lawmakers are trying to change that.

Written by Nicole Ludden and Hank Stephenson, Arizona Agenda

Originally published Mar 14, 2025

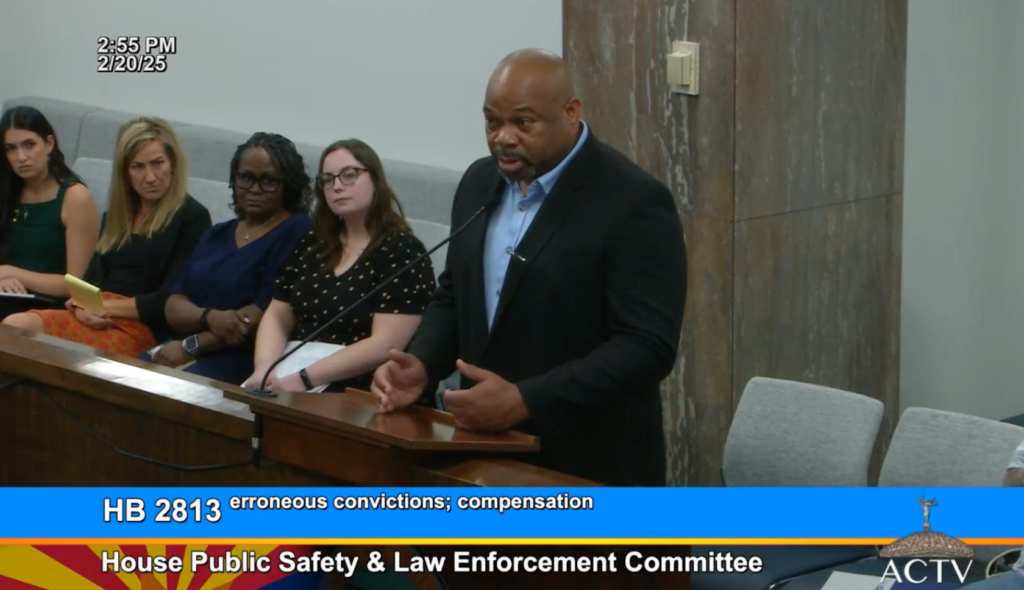

Khalil Rushdan served 15 years in an Arizona prison for a murder he didn’t commit.

In late February, thirteen years after he walked out of prison, Rushdan told state lawmakers that even after a judge determined he was wrongfully convicted, he left prison with the same resources he had when he was incarcerated at 22.

And Rushdan isn’t the only wrongfully convicted Arizonan who has been pushed back into society without redress for the time he lost.

Republican Rep. Pamela Carter asked him to estimate how much money he lost in those 15 years.

“I honestly couldn't even begin…” Rushdan said. “To only be able to see my mom four times before she passed … I can't begin to calculate.”

Rushdan’s daughter was six years old when he was sent to prison. She was a full-grown adult by the time he was freed. And his mother passed away eight months after he got out.

Calculating the loss incurred when the justice system steals parts of peoples’ lives is an impossible task. Arizona’s lawmakers are trying anyway.

Republican Rep. Khyl Powell’s HB2813 would allow those whose convictions are overturned to file a claim to receive 200% of the median household income for each year they were incarcerated. That 200% figure is currently about $154,000, per U.S. Census data.

But the compensation is calculated by what 200% of the median income was during each year of incarceration. When Rushdan went to prison in 1997, for example, that figure was about $80,000.

Currently, 39 states, the District of Columbia and the federal government have some sort of compensation statute for the wrongfully convicted.

The Arizona Justice Project has been working on bringing a restitution law here for nearly 20 years.

The nonprofit was formed in 1998 to provide legal assistance in post-conviction relief proceedings. The Justice Project has worked to free 51 people from incarceration, including Rushdan.

“You can never return them to where they started at before a wrongful conviction,” said Hope DeLap, the Justice Project’s strategic litigation counsel. “But to restore their ability to rebuild their lives from the point that they are released from prison … it is kind of an acceptance of responsibility as a state, as a whole, for those wrongful prosecutions and what it meant for their lives.”

Powell said the Justice Project brought him the bill, and he felt a personal connection to it. He used to minister in prisons and thinks several of the people he met were innocent.

“You realize that in many instances, they're going to serve their sentence and never be exonerated. And you just — just feel helpless,” he said.

This year’s restitution bill has made it farther than all previous attempts in recent history. No lawmaker has voted against it in the House.

Even Republican Rep. Alexander Kolodin, a lawyer known for his exacting scrutiny of legislation on legal procedures, got emotional when voting for the bill in a House committee.

In law school, he recalled, he had a torts professor who asked “What could I pay you to cut off your leg?”

“And of course, the answer to that is nothing. There's no amount of money. And she goes, ‘That's right, but money is the best the law can do,’” Kolodin said. “It's the best that we can do, and it's not enough. But we need to do it.”

To receive the money, someone who has been wrongfully convicted would have to file a claim in a superior court. The Attorney General’s Office would have the burden of proving the person filing the claim committed the offense and isn’t eligible for the money.

The payouts would come from the Arizona Department of Administration’s Risk Management Revolving Fund, which is basically the state’s insurance agent that pays out damages Arizona and its employees incur.

But the actual cost to the state is a guessing game. The Justice Project receives hundreds of requests for help every year, but actually overturning a conviction is rare. There are likely innocent people sitting in Arizona’s prisons who don’t have the legal and financial resources to fight their convictions.

“It's hard to say that the number of exonerees reflects the number of wrongful convictions. It's really the number of provable wrongful convictions that leads to relief in court,” DeLap said.

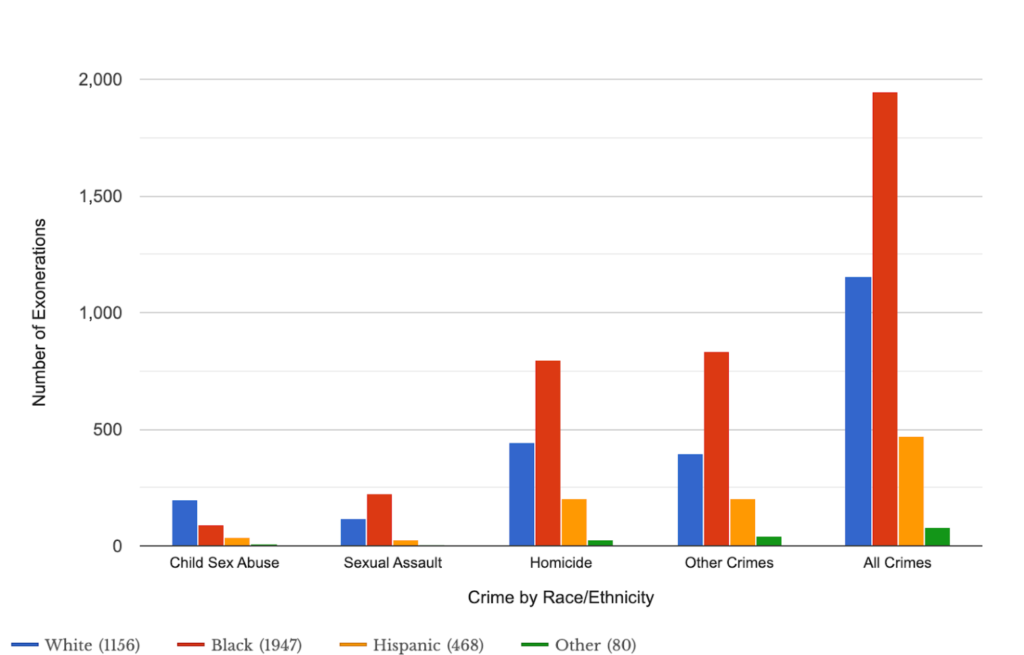

There is data on those who make it that far, however. Of the 153 wrongful convictions overturned across the United States in 2023, 84% of them were people of color, per the National Registry of Exonerations.

And 77% of those cases had documented instances of misconduct like false confessions, misleading evidence and ineffective counsel.

Some exonerated people can seek monetary relief through a federal civil rights action — but only if they can prove misconduct by someone on the other side of the courtroom. Police officers have qualified immunity that protects them from liability for constitutional violations in most cases. Prosecutors have absolute immunity and can’t be sued for actions related to a case.

Instead of pointing to a single bad actor, “the system as a whole fails this person by leading to a wrongful conviction,” DeLap said. But you can’t sue the entire criminal justice system.

Arizonans who are wrongfully convicted are stripped of their ability to receive an income, see their families and keep up with the ever-changing demands of society. They reenter the world without restitution when the government messes up.

“They're incarcerating them because they're holding them accountable for their actions. So shouldn't we apply the same principle of holding the state or institutions or agencies or departments accountable as well when they make mistakes?” Powell said.

In addition to financial compensation, the bill lays out a process for officially making someone un-guilty. Court-ordered conviction reversals don’t always erase incriminating information.

If someone wins a claim, the bill says all state and federal records of their convictions have to be expunged, the Arizona Department of Public Safety has to destroy their biological samples and the state Department of Corrections has to seal their conviction information.

The bill also attempts to make up for lost time beyond direct financial restitution.

The state would have to pay for 52 hours of mental health treatment, 120 credit hours’ worth of higher education and up to four financial planning or literacy classes. Those are directly intended for “all sorts of collateral consequences” a wrongful conviction creates, DeLap said.

Rushdan told a radio show getting out of prison was like “traveling 15 and a half years into the future.”

“I get out, and the first thing, you're observing people — but everybody is looking down at their hands. What is everybody doing? Like, is this a zombie apocalypse or whatever? But I didn't realize, like, people were looking at their phone, their smartphones, using a debit card, things like that,” he said. “That's kind of like the release side of things, just overwhelmed with anxiety, and then released into this new world.”

Even though all the lawmakers who’ve voted on the restitution bill so far have supported it, not everybody is on board. Maricopa County Attorney Rachel Mitchell said the bill confuses “not guilty” with “factually innocent.” Powell, the bill sponsor, said her office hasn’t reached out to him.

“This bill, if passed into law, would allow people convicted of a horrendous crime to sue if their conviction is overturned for legal (not factual) reasons if they cannot be retried,” Mitchell told us in a written statement. “There are many reasons retrials would be difficult — for example, if a key witness had passed away or could not be found for the retrial.”

DeLap called that a “mischaracterization.” The bill provides an opportunity for the state to prove someone isn’t factually innocent.

“Wrongful convictions occur. The criminal legal system is operated by humans and errors are made,” DeLap said. “Our focus should be on how to address the harms caused by a wrongful conviction for both the exoneree and original crime victim.”